1918 Spanish Flu Pandemic: Parallels, Differences, and US Health Challenges

The 1918 Spanish Flu Pandemic offers crucial historical context for understanding present-day health crises in the US, revealing vital lessons for public health responses and preparedness strategies.

Analyzing the 1918 Spanish Flu Pandemic: Parallels and Differences with Current Health Challenges in the US provides critical insights into how historical health crises can inform our approach to modern-day public health. As current events unfold, understanding past pandemics becomes increasingly vital for effective disease management and societal resilience.

The Unseen Enemy: 1918 Pandemic’s Initial Impact

The 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic emerged rapidly, sweeping across the globe with devastating speed and claiming an estimated 50 million lives worldwide, including approximately 675,000 in the United States. Its initial impact was characterized by a lack of understanding regarding the pathogen, limited medical interventions, and widespread societal disruption. This immediate and profound effect set a somber precedent for future public health emergencies.

Early reports from the period, as documented by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), highlight the rapid onset of severe respiratory symptoms and a high mortality rate, particularly among young adults. This demographic anomaly, where healthy individuals succumbed to the virus, distinguished it from typical influenza outbreaks that disproportionately affected the very young and the elderly.

Rapid Global Spread

The flu’s rapid global spread was facilitated by troop movements during World War I, transforming localized outbreaks into a worldwide catastrophe. Ports and military camps became epicenters, quickly disseminating the virus across continents.

- Troop Movements: WWI significantly accelerated viral transmission.

- Lack of Air Travel: Despite no modern air travel, ships ensured global reach.

- Overwhelmed Infrastructure: Healthcare systems were quickly saturated.

The absence of effective communication and coordinated international responses further exacerbated the crisis. Local communities often implemented their own, sometimes inconsistent, measures to combat the spread, leading to varied outcomes across different regions.

Public Health Responses: Then and Now

Examining public health responses during the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic reveals both stark differences and surprising similarities to current health challenges in the US. Then, as now, authorities grappled with balancing individual liberties against collective health needs, often facing public skepticism and economic pressures.

In 1918, interventions primarily focused on non-pharmaceutical measures due to the absence of vaccines or antiviral treatments. These included quarantines, isolation, public gatherings bans, and mask mandates. Cities like St. Louis, which implemented early and stringent measures, generally fared better than those like Philadelphia, which delayed action.

Key Differences in Response Capabilities

Modern public health infrastructure benefits from significant advancements in science, technology, and global coordination. The development of rapid diagnostic tests, effective vaccines, and targeted antiviral therapies represents a monumental shift.

- Vaccine Development: No vaccine existed for the 1918 flu; modern pandemics see rapid vaccine deployment.

- Antiviral Treatments: Current challenges often have specific antiviral medications.

- Global Surveillance: Advanced systems track outbreaks in real-time.

Despite these advancements, challenges persist in vaccine distribution, public acceptance, and addressing misinformation. The speed of information dissemination, both accurate and inaccurate, has also dramatically changed, adding a new layer of complexity to public health messaging.

Societal Impact and Economic Disruptions

The 1918 pandemic caused profound societal and economic disruptions, mirroring many of the issues faced during recent health crises. Businesses closed, schools shut down, and daily life came to a standstill in many areas, leading to significant economic downturns and social upheaval.

Labor shortages became rampant as illness incapacitated large segments of the workforce. Essential services struggled to maintain operations, and the economy experienced a sharp, albeit temporary, contraction. The psychological toll on communities, marked by grief and fear, was also immense and long-lasting, as reported in historical journals.

Economic Fallout: Historical Insights

The economic impact of the 1918 flu was severe, leading to closures and reduced productivity. However, the global economy was also grappling with the end of World War I, making it challenging to isolate the flu’s exact financial consequences.

- Workforce Depletion: High mortality rates led to severe labor shortages.

- Business Closures: Non-essential businesses shuttered, impacting local economies.

- Supply Chain Disruptions: Production and distribution were heavily affected.

Today, economic models are more sophisticated, allowing for better projections and mitigation strategies during health emergencies. However, the fundamental tension between public health measures and economic stability remains a central challenge, often leading to contentious public debate and policy dilemmas.

Medical Advancements and Scientific Understanding

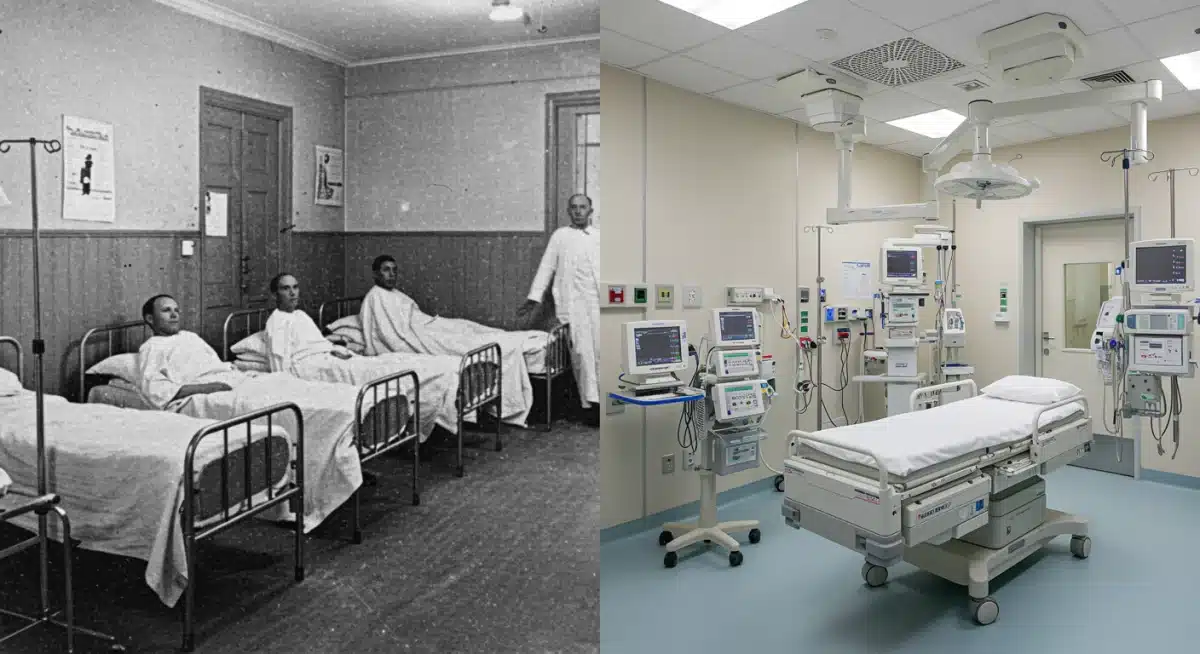

One of the most significant differences between the 1918 Spanish Flu and current health challenges lies in medical advancements and our scientific understanding of disease. In 1918, the concept of a virus was still relatively new, and diagnostic tools were rudimentary. Treatments were largely supportive, focusing on symptom management rather than targeting the pathogen directly.

Today, molecular biology, genomics, and advanced imaging have revolutionized our ability to identify, track, and combat infectious diseases. The ability to sequence a pathogen’s genome rapidly, develop targeted vaccines within months, and produce specific antiviral drugs represents a paradigm shift in pandemic response capabilities. This scientific leap is a cornerstone of modern public health.

Evolution of Diagnostic Tools

The diagnostic landscape has transformed from basic clinical observation in 1918 to sophisticated laboratory tests that can identify specific pathogens with high accuracy and speed.

- Viral Isolation: Not possible in 1918; routine today.

- PCR Testing: Rapid and accurate pathogen identification.

- Genomic Sequencing: Tracks viral evolution and spread in real-time.

This enhanced understanding allows for more precise public health interventions, better patient management, and the development of more effective treatments. The ongoing research into broad-spectrum antivirals and universal vaccines further illustrates the continuous scientific pursuit to better prepare for future pandemics.

Ethical Dilemmas and Social Equity

Both the 1918 Spanish Flu and recent health challenges have exposed profound ethical dilemmas and issues of social equity within the US. In 1918, access to care, information, and even basic necessities was often unequal, exacerbating the impact on marginalized communities. Historical accounts suggest that racial and socioeconomic disparities played a significant role in mortality rates and recovery outcomes.

Today, while awareness of health equity is higher, disparities persist. Debates surrounding vaccine access, treatment allocation, and the disproportionate impact of diseases on certain demographic groups remain central to public health discourse. These discussions underscore the ongoing need for policies that prioritize fairness and inclusivity in health emergency responses.

Addressing Health Disparities

Modern public health efforts aim to mitigate disparities through targeted outreach, equitable resource distribution, and culturally competent communication strategies, a stark contrast to the less formalized approaches of a century ago.

- Equitable Access: Ensuring fair distribution of vaccines and treatments.

- Community Engagement: Tailoring health messages to diverse populations.

- Policy Advocacy: Addressing systemic inequalities in healthcare.

The lessons from 1918 emphasize that a pandemic’s true impact is not just biological but also deeply social and ethical. Future preparedness must integrate robust strategies to ensure that all segments of society are protected and supported, regardless of their background or socioeconomic status.

Long-Term Health and Preparedness Strategies

The long-term health consequences of the 1918 Spanish Flu, though less documented with modern scientific rigor, included chronic fatigue and neurological issues in some survivors. This historical context informs current understanding of post-acute infection syndromes, highlighting the need for comprehensive follow-up care and research into long-term health impacts.

For preparedness, the 1918 pandemic underscores the importance of robust public health infrastructure, continuous investment in scientific research, and adaptable response plans. The US now has agencies like the CDC and HHS, dedicated to disease surveillance and emergency response, a significant improvement from the fragmented approach of a century ago.

Building Resilient Health Systems

Developing resilient health systems means not only having the tools but also the organizational capacity and political will to deploy them effectively during a crisis. This involves cross-sector collaboration and international partnerships.

- Strategic Stockpiling: Maintaining reserves of essential medical supplies.

- Workforce Training: Ensuring a skilled and sufficient healthcare workforce.

- Public Communication: Establishing clear, consistent, and trusted information channels.

The ongoing analysis of past pandemics, such as the 1918 Spanish Flu Parallels, is crucial for refining these strategies. It helps policymakers and public health officials anticipate challenges, learn from past mistakes, and build a more resilient and equitable health system for future generations, ultimately safeguarding national security.

| Key Point | Brief Description |

|---|---|

| Pathogen Knowledge | 1918 lacked viral understanding; modern science rapidly identifies and sequences pathogens. |

| Intervention Tools | 1918 relied on non-pharmaceuticals; today, vaccines and antivirals are key. |

| Public Health Infrastructure | Fragmented in 1918; now, centralized agencies and global surveillance exist. |

| Societal Impact | Both eras faced economic disruption and social inequities, highlighting persistent challenges. |

Frequently Asked Questions About Pandemic Parallels

The 1918 Spanish Flu’s high mortality stemmed from several factors, including its virulence, lack of medical treatments, and secondary bacterial pneumonia. The virus disproportionately affected healthy young adults, leading to severe lung damage and rapid death in many cases, overwhelming healthcare systems globally.

In 1918, public health measures primarily involved non-pharmaceutical interventions like quarantines, mask mandates, and social distancing due to the absence of vaccines or antivirals. Today, we utilize these alongside rapid vaccine development, advanced diagnostics, and targeted antiviral treatments for a more comprehensive approach.

World War I significantly accelerated the 1918 pandemic’s global spread. Large-scale troop movements, crowded military camps, and wartime conditions created ideal environments for the virus to mutate and transmit rapidly across continents, transforming localized outbreaks into a worldwide catastrophe.

While less scientifically documented than modern post-viral syndromes, historical accounts suggest some 1918 Spanish Flu survivors experienced long-term health issues, including chronic fatigue and neurological problems. This historical experience informs current research into post-acute sequelae following viral infections, emphasizing comprehensive follow-up care.

The 1918 pandemic highlighted significant social inequities, with marginalized communities often facing unequal access to care and resources. Lessons emphasize the critical need for inclusive public health policies, equitable distribution of interventions, and culturally sensitive communication to ensure fair protection and support for all populations during health crises.

Looking Ahead: Building a Resilient Future

As we continue Analyzing the 1918 Spanish Flu Pandemic: Parallels and Differences with Current Health Challenges in the US, the focus shifts to how these historical insights shape future preparedness. The ongoing evolution of infectious diseases means that continuous vigilance, scientific innovation, and robust public health infrastructure are not merely aspirational but essential. Policymakers are actively reviewing strategies to enhance rapid response capabilities, improve global collaboration, and address persistent health disparities. The goal is to move beyond reactive measures towards proactive, integrated systems that can effectively safeguard public health against unforeseen threats, minimizing both immediate and long-term societal impacts. This involves sustained investment in research, healthcare workforce development, and public trust in scientific institutions.